|

part of the world, seeing the same images at the same moment gives a sense of equality. Things [in African cinema] have changed, fortunately, otherwise there would have been little use in me continuing."

"We have completely entered the modern world, and it is really quite incredible. I never dreamed that making films could change the course of history, and I can assure you that is the most beautiful present anyone could have given me."

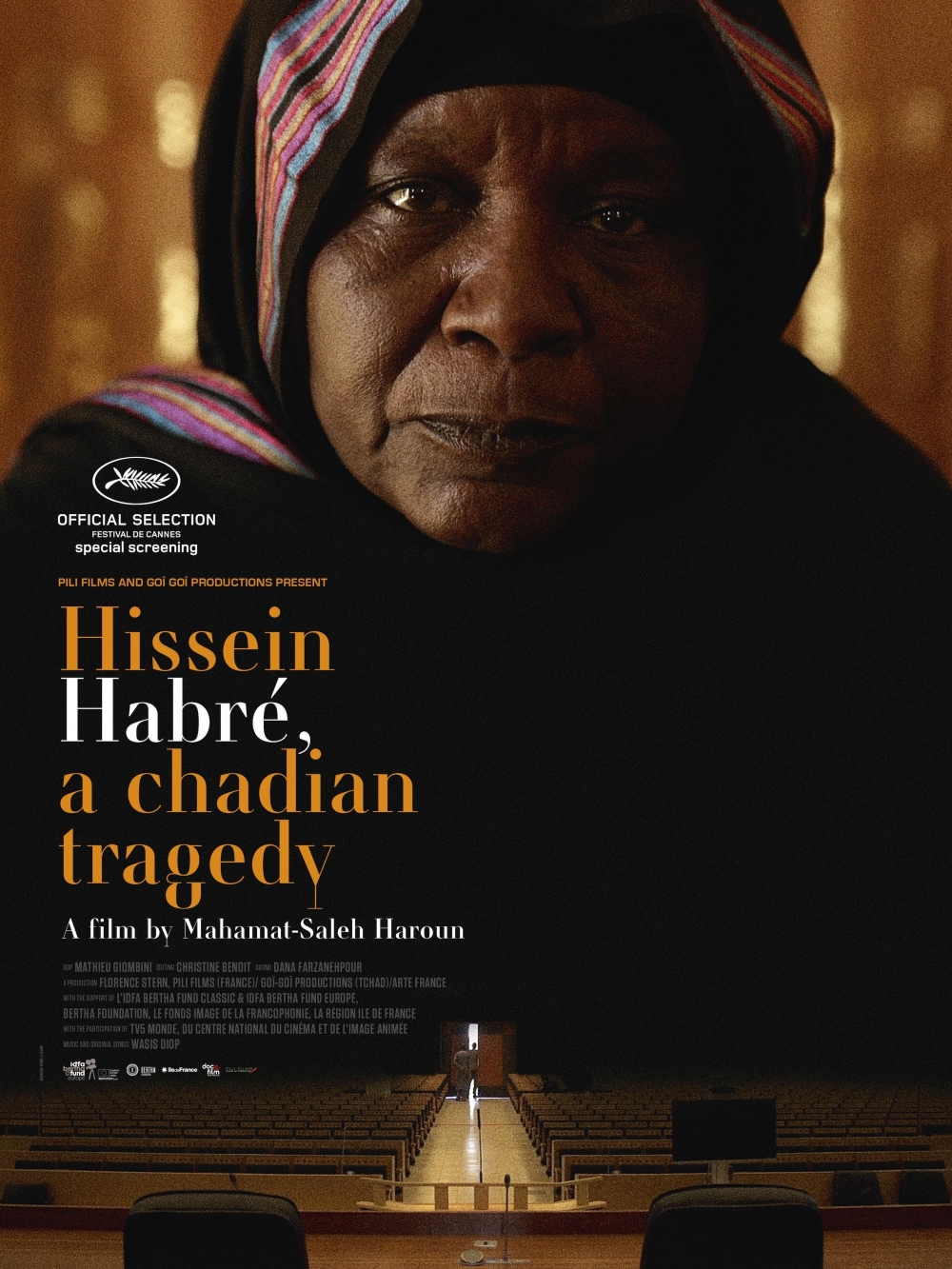

"The award at Cannes has had an incredible effect in the sense that it has practically catapulted the role of cinema and the importance of cinema, even to a political level in Chad," he said.

I may live in France, but my home is in Chad," he said. "Because I really love this country, I really love its people … the people I tell stories about seem to be real. The most rewarding thing is that when I show my films over there, the people have this impression. They told me: 'That's it, you're talking about us.'"

"That a film can change the course of history in a country like Chad, I find that extraordinary." Asked if he was therefore, confident about the future of African

|

|

cinema, Haroun said: "Pan-Africanism is dead, and we must bury it. And if it is dead there is no African cinema. There is cinema in each country. We have to create a new utopia, where if one country can manage to create films, other countries can follow."

"I laugh when I see African comedies because things are so serious. Do you think we need that in Africa? When we have things like in Mali happening? Cinema can't be a luxury, it can't be an art of entertainment. That's a luxury we should leave to others, but not Africans."Dismissing Nollywood, the film industry centred in Nigeria, as a "monster" aping a money obsessed Hollywood, he said: "Film-makers must wake people up, and take part in thinking about Africa's future. They must push our capacity to think about our own destiny."

Now, Selah-Haroun is the minister of culture in his country chad. He is working on a project,

An International film school in his country, says "From the moment the school opens we will have technicians, actors, an entire industry that will completely change our offering. It will create a whole new economy around cinema in Chad, that's what I'm working towards."

|

Haroun, Cultural Minister, Chad with Irina Bokova,UNESCO

|